To ensure that no one is left without life’s essentials, while also ensuring that we collectively do not overshoot our pressure on the Earth’s life-supporting systems that we fundamentally depend on, English economist Kate Raworth introduced the concept of Donut Economics in 2012, an economic model designed to fit the 21st century.

Donut Economics is a new vision for an economic model. By rethinking our systems, the goal of national and global economies can shift from simply increasing GDP to creating a society that can provide enough goods and services for all while using the Earth’s resources in a way that does not threaten our future security and prosperity.

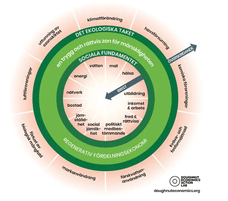

This model consists of a dashboard with indicators that define its boundaries. Imagine looking at a donut from above. You would see a healthy green region, which is the circular donut. The outer edge represents the ecological ceiling, while the inner edge reflects the social foundation.

The hole in the donut reveals the boundary at which people have achieved the essentials of life, such as food, water, healthcare, and freedom of expression. If we exceed or misuse our planetary resources, the model would indicate that we cannot ensure the necessary social foundations are met among citizens. In real terms, this means people living without access to abundant food, clean water, and essential healthcare. Thus, a significant challenge for humanity is to get everyone out of the hole.

At the same time, overexploitation of the Earth’s renewable resources would lead to catastrophic consequences such as water scarcity, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, and ultimately climate change.

In our current systems, aspects like the increase in healthcare costs due to rising air pollution are ”externalities” not accounted for in production and consumption costs, whereas in an embedded economy that allows us to view the economy as embedded in larger social and ecological webs, these costs are considered.

At its core, Donut Economics is based on an economy that is both renewable and distributive in its design. It has huge implications for all groups negotiating the balance between economic growth and powerful social change. Nations can begin to adopt a zero-tolerance strategy with strong regulatory oversight to halt activities that harm our planet and undermine societal health. Embracing tax policies and public expenditures can help address inequality by stimulating shifts away from wealth and resource extraction, and directing it towards creating jobs and wealth redistribution. There could also be more collaboration between the public and private sectors, especially to bring about a sustainable model at an industrial scale necessary to create a circular and renewable economy. To date, over 150 countries have used the Donut Economics model. In fact, Amsterdam already implemented Donut Economics in early April last year after the Netherlands had one of the world’s highest mortality rates from the coronavirus pandemic. The model was scaled down to provide a ”city portrait” that not only revealed areas where basic needs were not being met and planetary boundaries were being exceeded, but also how these issues are interconnected. Because of the model, issues were addressed directly, including carbon emissions from imports and exploitation of West African labor. By formally adopting the theory, the city’s government hoped to recover from the crisis and prevent future crises.

The model takes into account that human behavior can be cooperative and caring, just as it can be competitive and individualistic. It also acknowledges that economies, societies, and the rest of the living world are complex, mutually dependent systems best understood through the lens of systems thinking. It requires that today’s economies aim to provide enough material and services for everyone while using the Earth’s resources in a way that does not threaten our future security and prosperity.

The ultimate goal of this framework is to enable communities to make positive choices and live in balance to thrive economically, socially, and environmentally. This new economic vision cannot be achieved by an individual or a single organization. Instead, it requires intention, planning, collaboration, and contributions from all stakeholders. What the monk offers is a metaphor that helps us visualize an economic system that could create a thriving society today and preserve a habitable planet for all future generations.

What is Donut Economic Model?

Raworth arrived at the ”doughnut” image by describing two circles, one inside the other. The outer circle is inspired by a diagram she came across while working for the non-profit organization Oxfam against poverty. There, a group of earth system scientists looked at the environmental conditions that make life on earth possible. Together, they identified a set of ”planetary boundaries” which, if crossed, would permanently damage the climate, land, oceans, biological diversity, and consequently the conditions for human life. This outer ring relates to issues such as climate change, air pollution, loss of biodiversity, depletion of the ozone layer, and ocean acidification.

While Raworth recognized the importance of striving to stay within this ecological ceiling, she also understood that this is only one side of the issue. If the outer ring described a maximum, she also introduced an inner ring to represent the minimum conditions that everyone needs to lead a good life. Derived from the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Agenda 2030), the inner ring addresses urgent issues such as access to food and clean water, adequate housing, energy, healthcare, education, social justice, the right to a political voice, fairness and opportunities for work and income.

The goal is to live in balance with these two sets of conditions, to achieve the desirable space between the monk’s inner and outer ring, between the upper ecological ceiling and the foundational social foundation. Raworth’s theory is specific in describing the end result, but it does not prescribe a recipe for achieving it. Instead, it challenges stakeholders to look at the whole picture and understand the effect of their decisions on multiple factors.

.